Hero of World War II and Korea

The most decorated Marine in Corps History

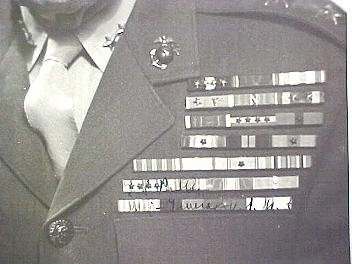

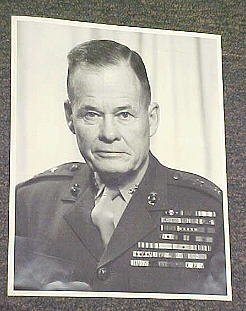

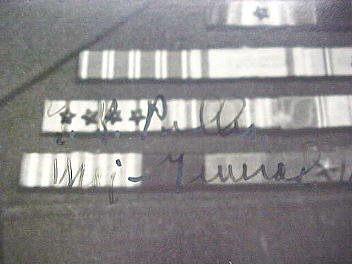

Signed 11" by 14" vintage photo

Signed Maj General L.B. Puller USMC

as a Two Star Major General

Photo was signed between September 1953 and November 1955

when Puller was a 2 Star Major General

VERY RARE

$1995

SOLD

This 11" by 14" vintage photo is in fantasic condition

Puller signed anything is extremely rare not to mention

a beautifally signed large vintage photo

See a signed Puller autobiography we sold here

An interesting article on Chesty Puller

Lewis Burwell Puller

'CHESTY' PULLER

Everyone Needs a Hero

Story by Staff Sgt. Kurt M. Sutton

HQMC, Washington

Marine Magazine, August 1998

Another fresh-faced kid entered the Virginia Military

Institute in 1917. In August 1918, he dropped out and enlisted in the Marine

Corps, hoping to join the fighting in Europe during the World War. He never

saw combat. Instead he was appointed a Marine Reserve lieutenant, only

to be placed on the inactive list 10 days later due to post-war drawdowns.

Determined to be a Marine, he rejoined the Corps as an enlisted man, hoping

this time to take part in the fighting in Haiti.

Born June 26, 1898, in West Point, Va., the young man

grew up hunting and listening to tales of the Civil War told by his relatives.

He also had a heavy appetite for reading, pouring through count-less books

of military tales and history.

Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller would go on to earn five Navy

Crosses, the nation’s second highest award for valor, and spend 37 years

in the Corps, retiring at the rank of lieutenant general.

Jungle Combat

Puller’s service in Haiti allowed him to cut his "battle

teeth," leading patrols and engaging the Caco rebels in more than 40 engagements.

He witnessed Haitian discipline during drill and patrols, observations

which no doubt influenced his own distinct style of leadership.

After Haiti, Puller was again commissioned a second lieutenant.

In 1930, he and his Marines found new action patrolling the jungles of

Nicaragua with Guardia Nacional troops against rebels led by Augusto Cesar

Sandino. His actions there earned him his first Navy Cross.

Puller’s growing reputation gained him a seat at the

Army Infantry School at Fort Benning, Ga. During one of his classes, which

was peppered with future notable Army and Marine Corps generals, Puller

engaged in a heated discussion on volumes of fire with the instructor.

One of his most famous quotes came from that discussion, culminating with

Puller yelling, "You can’t hurt ‘em if you can’t hit ‘em."

In July of 1932, Puller returned to Nicaragua, where

the newspapers heralded his arrival with the headline: "Marines Bring Back

the Tiger of Segovia to Fight Sandino." Sandino welcomed the news by putting

a bounty of 5,000 pesos on Puller’s head. Puller earned his second Navy

Cross during this tour in Nicaragua and was known thereafter as the "Tiger

of the Mountains."

To say that "Chesty" was already a Marine Corps legend

might be too strong. Certainly, he was very well known. A San Francisco

newspaper dated Feb. 11, 1933, was headlined Most Decorated Marine Will

Go to Shanghai."

In early 1933, Puller joined the China Marines at the

American Legation in Peiping. He served mainly as the commander of the

"Horse Marines," a unit of 50 men who rode magnificent Manchurian ponies

on patrol and parade duties. While there, he had the opportunity to observe

the Japanese infantry in training and to learn the sport of polo.

After several more tours, including sea duty, he was

reassigned to China as commander of the 4th Marine Regiment until August

1942.

Another War

Returning to battle in October 1942, Puller, now a lieutenant

colonel, commanded 1st Battalion, 7th Marines during the battle for Guadalcanal.

Nearly 1,400 Japanese were killed and 17 truckloads of equipment taken

while Puller’s battalion defended a mile-long front against an estimated

3,000 attackers. Puller was awarded his third Navy Cross.

During the fighting, Puller could often be seen at the

front leading his Marines. He often disregarded enemy fire while others

chose to duck and cover. At one point, a grenade landed within eight feet

of Puller. While others hit the ground, Puller is alleged to have said,

"Oh, that. It’s a dud."

Shortly after the battle for the ‘Canal,’ Puller became

the executive officer of the 7th Marine Regiment. In January 1944, on the

island of New Britian, he took command of two battalions whose commanding

officers had been taken out of the fight, reorganized them while under

heavy machine-gun and mortar fire, and led the Marines in an attack against

the enemy’s heavily fortified position. These actions earned Puller a fourth

Navy Cross.

As commander of the 1st Marine Regiment, he led his Marines

in one of the bloodiest battles of the war on Peleliu during September

and October 1944. King Ross remembers Puller vividly.

"I was a radio operator on Peleliu with the 3rd Battalion.

During the battle, we’d captured a Japanese machine gun. He walked up to

us and asked ‘What the hell is that?’ We told him, and he asked us if we

could get him one," recalled the 71-year-old Ross. "Two days later we got

him his machine gun.

"We had all heard that he had issued an order that all

officers would eat after the enlisted. We got the idea that he never forgot

that he was a sergeant. That’s why we all would have gone to hell with

him if he’d asked us," said Ross, "and we just about did!"

In the battle for Peleliu, Puller’s regiment sustained

a 56 percent casualty rate while going up against the toughest section

of the island, a series of hills, caves, and jungle known as "Bloody Nose."

Puller’s battered and bloodied 1st Marines had to be removed from the fight

and replaced by the 7th Marines.

In his speech notes from 1978, retired Brig. Gen. Edwin

Simmons, director emeritus, Marine Corps Historical Division, described

seeing ‘Chesty’ for the first time when Puller came to talk to officers

candidates at Quantico, Va., in 1942.

"This was the man we were going to hear speak ... not

very tall, he stood with a kind of stiffness with his chest thrown out,

hence his nickname ‘Chesty.’ His face was yellow-brown from the sun and

atabrine, the anti-malaria drug that was used then. His face looked, as

someone has said, as though it were carved out of teakwood. There was a

lantern jaw, a mouth like the proverbial steel trap, and small, piercing

eyes that drilled right through you and never seemed to blink."

Puller was then 44 years old. The four-time Navy Cross

recipient would not see combat again during World War II; instead, he was

assigned back to the United States in November 1944.

He was sent to Camp Pendleton, Calif., in August 1950

to take command of his old unit, the 1st Marines, which was gearing up

for Korea.

Cold Hell

Puller landed with the 1st Marines at Inchon, Korea,

in September 1950. Aboard his landing craft was Lt. Carl L. Sitter, who

would earn the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor, for

his actions during Nov. 29-30, 1950, at Hagaruri.

"I was on his landing craft that day. I’d been given

responsibility for the headquarters section and later acted as liaison

with the 5th Marine Regiment. Sometime after we were at Tent Camp 2, I

had to go to his tent to talk to him. When I went inside, it was dark,

and it took my eyes awhile to adjust. When they did, I noticed him sitting

on the ground snapping in with his pistol; he was pointing it right at

me.

"He was ramrod straight with a stubby pipe in his mouth

all the time. He was approachable. He’d often say ‘Hello son, how are you

doing?’ when he came across a Marine."

While "attacking in a different direction" at the Frozen

Chosin Reservoir Dec. 5-10, 1950, Puller earned his fifth and final Navy

Cross. Ten Chinese Divisions had been sent to annihilate them, but the

Marines smashed seven of the divisions during their retrograde to the sea.

Facing attack from all sides, including two massive enemy attacks on the

rear guard, Puller’s direct leadership ensured all casualties were evacuated,

all salvageable equipment was brought out, and ensured there was enough

time for the column to reach its destination.

In addition to the Navy Cross for his actions during

the breakout, he was awarded the Army’s equivalent — the Distinguished

Service Cross. In January 1951, Puller was promoted to brigadier general

and appointed as assistant commander of the 1st Marine Division.

Promoted to major general in September 1953, Puller assumed

command of the 2nd Marine Division at Camp Lejeune in July 1954. It was

here he suffered what was originally described as a mild stroke. After

many examinations, Puller was declared fit for duty by his military doctors

aboard the base.

But Puller’s state of health remained a controversial

subject and led to his forced retirement. Thwarting tradition, he had a

sergeant major who had worked for him in more glorious days, pin on his

third star before he retired Nov. 1, 1955.

His 14 personal decorations, excluding those from foreign

governments, certainly are part of Puller’s enduring lore, but perhaps

the stories of his leadership, courage, honor, and fighting ability are

his most important legacy. They serve as reminders and inspiration to generations

of Marines that leading by example is the most important trait we can possess.

Lewis B. "Chesty" Puller died Oct. 11, 1971, at the age of 73.